What Is Medication-Induced Delirium?

Delirium isn’t just being forgetful or confused. It’s a sudden, sharp change in thinking that can happen over hours or days-often because of a medication. In older adults, especially those over 65, it’s one of the most common reasons someone ends up in the hospital confused, agitated, or strangely quiet. Unlike dementia, which slowly gets worse over years, delirium comes on fast. And unlike depression, it’s not a mood issue-it’s a brain function problem.

Medication-induced delirium is the most frequent reversible cause. That means if you catch it early and stop the offending drug, the person can get back to normal. But if it’s missed, the consequences are serious: longer hospital stays, higher risk of death, and lasting cognitive damage. One study found that older adults with delirium stay in the hospital an average of eight extra days. Their chances of recovering strength and memory six months later drop by half.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not every older adult will get delirium from meds, but some are far more vulnerable. People over 85 are more than twice as likely to develop it compared to those in their mid-60s. Those with existing dementia, Parkinson’s, or a past episode of delirium are at even higher risk. And it’s not just about age-it’s about how many meds they’re on.

Taking three or more medications with anticholinergic effects increases delirium risk by nearly five times. Anticholinergic drugs block acetylcholine, a brain chemical critical for memory and attention. These include common over-the-counter sleep aids like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), bladder medications like oxybutynin, and even some antidepressants like amitriptyline. Even if a doctor prescribes them, they’re often unnecessary in older adults.

Another big risk group: those on benzodiazepines. Drugs like lorazepam (Ativan) or diazepam (Valium) are often given for anxiety or sleep, but they can trigger delirium in older patients within 24 to 72 hours. One study showed that patients who took benzodiazepines before going into the ICU were nearly three times more likely to develop delirium. And once it starts, the delirium lasts longer-by over two days on average.

How to Recognize the Signs

Delirium doesn’t always look like someone screaming or thrashing around. In fact, the most common type in older adults is hypoactive delirium-it’s quiet, withdrawn, and easy to mistake for tiredness, depression, or just "getting older."

- They seem unusually quiet, drowsy, or unresponsive

- They stop eating, talking, or engaging with family

- They stare blankly or don’t follow simple conversations

- They’re harder to wake up or seem "in another world"

Hyperactive delirium-where someone is restless, yelling, or hallucinating-is rarer but more obvious. Mixed delirium flips between the two. The key is change: if your loved one was sharp and alert yesterday, and today they’re blank or agitated, that’s a red flag.

Family members often report: "They’re not themselves." One study found 89% of caregivers noticed a complete personality shift within 48 hours of starting a new high-risk medication. That’s your signal to act-not to wait and see.

Top Medications That Cause Delirium

Some drugs are far more dangerous than others for older adults. Here’s the shortlist of biggest offenders:

- First-gen antihistamines: Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine-these are in many sleep aids and cold meds. They’re strong anticholinergics.

- Benzodiazepines: Lorazepam, diazepam, alprazolam. Even short-term use can trigger delirium.

- Opioids: Morphine and meperidine are high-risk. Hydromorphone is a safer alternative.

- Bladder meds: Oxybutynin, tolterodine-used for overactive bladder, but often unnecessary.

- Antidepressants: Amitriptyline, imipramine, paroxetine-especially older tricyclics.

- Newer risks: Ciprofloxacin (an antibiotic) and quetiapine (an antipsychotic) were added to high-risk lists in 2023 due to unexpected brain effects.

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria® lists 56 medications to avoid in older adults. If your loved one is on any of these, ask: Is this still needed? Can we try something safer?

How to Prevent It

Prevention isn’t about avoiding all meds-it’s about choosing smarter ones and watching closely.

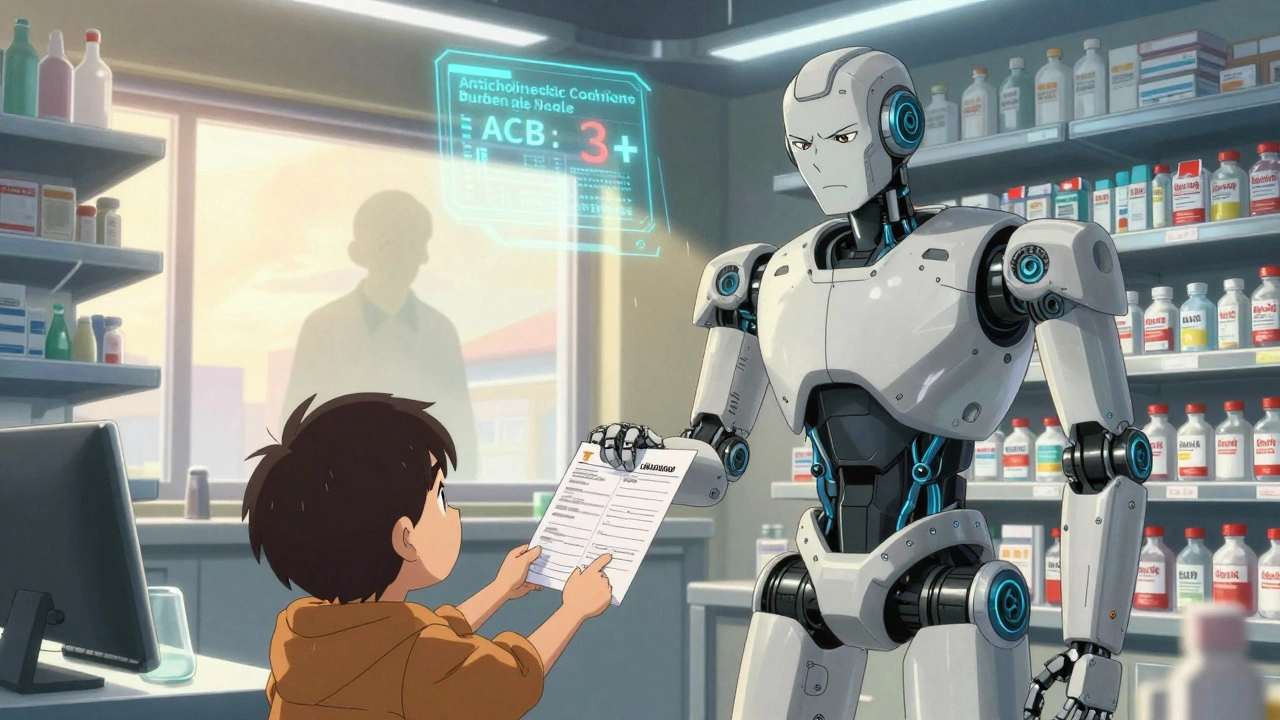

- Do a full med review. Every six months, sit down with the doctor or pharmacist and ask: "Which of these are still necessary?" Use the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (ACB). A score of 3 or higher means high risk.

- Replace high-risk drugs. Swap diphenhydramine for loratadine (Claritin). Use non-benzodiazepine sleep aids like melatonin (in low doses) or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia.

- Use non-drug pain control. Combine acetaminophen with heat, massage, or physical therapy. This cuts opioid use by nearly 40%, lowering delirium risk.

- Taper slowly. Never stop benzodiazepines or opioids cold turkey. Withdrawal can cause delirium too. Work with a doctor to reduce doses over 7-14 days.

- Ask about screening. Hospitals that use the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) catch delirium early. Ask if they screen daily for it.

The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), used in over 200 U.S. hospitals, cuts delirium by 40% using simple steps: keeping the person oriented, encouraging movement, ensuring sleep, and avoiding unnecessary meds. You don’t need a fancy program-just consistent attention.

What to Do If You Suspect Delirium

If you notice sudden confusion, don’t wait. Call the doctor immediately. Bring a full list of all medications-including supplements and OTC drugs. Say: "I think this might be medication-induced delirium. Can we review what they’re taking?"

Don’t assume it’s dementia getting worse. Don’t assume it’s just aging. Don’t accept sedation as a solution. The goal is to find and remove the trigger. Often, once the drug is stopped, the person improves within days.

Keep a log: When did the change start? What new meds were added? Did they have an infection or fall recently? This info helps doctors rule out other causes like UTIs or low sodium.

Why This Matters Beyond the Hospital

Medication-induced delirium isn’t just a hospital problem. It happens in nursing homes, during home care, and even after a pharmacy refill. In the U.S., it affects 2.6 million older adults every year-and costs $164 billion. Many cases are preventable.

Since 2018, Medicare has stopped paying hospitals for complications from delirium, calling it a "never event." That’s pushing hospitals to change. But families still need to be the frontline defenders.

Older adults aren’t just more sensitive to drugs-they’re often prescribed them without enough scrutiny. A 2023 study found 43% of hospitals still routinely give high-risk meds to seniors. That’s not normal. It’s not okay.

Looking Ahead

There’s new hope. The FDA now requires stronger warnings on anticholinergic labels. The National Institute on Aging is funding real-time EHR tools that flag dangerous drug combinations before they’re prescribed. AI systems are being tested to predict delirium risk with 84% accuracy.

But the most powerful tool is still you. Knowing the signs. Asking the questions. Pushing back when a prescription feels wrong. Because when it comes to delirium, speed saves brains.

Can over-the-counter meds cause delirium in older adults?

Yes. Common OTC meds like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), and even some sleep aids and cold medicines have strong anticholinergic effects. These are among the top causes of medication-induced delirium. Many older adults take them without realizing the risk. Always check the active ingredients and talk to a pharmacist before giving any OTC drug to someone over 65.

Is delirium the same as dementia?

No. Dementia is a slow, progressive decline in memory and thinking that lasts months or years. Delirium is sudden, fluctuating, and often reversible. Someone with dementia can still have delirium on top of it-and that’s especially dangerous. Delirium can accelerate dementia progression and cause permanent brain changes if not treated quickly.

Why is hypoactive delirium often missed?

Because it looks like tiredness, depression, or just being quiet. People assume the person is just "slowing down with age." But hypoactive delirium affects 72% of cases in older adults. The person may sit silently, not respond to questions, or stop eating. Without training, even nurses miss it. That’s why caregivers need to speak up when something feels "off."

Can switching medications help prevent delirium?

Absolutely. Replacing high-risk drugs with safer alternatives is one of the most effective prevention strategies. For example, switching from diphenhydramine to loratadine for allergies, or from morphine to hydromorphone for pain, can cut delirium risk significantly. Always ask: "Is there a lower-risk option?"

What should I bring to a doctor’s appointment about delirium?

Bring a complete list of every medication-including vitamins, supplements, and OTC drugs. Include doses and when they were started. Note any recent changes in behavior, sleep, eating, or mobility. Write down when the confusion started and what happened before it began. This helps the doctor rule out infections, dehydration, or other causes and focus on medication triggers.

Adrianna Alfano

December 4, 2025 AT 09:53Casey Lyn Keller

December 5, 2025 AT 23:45Jessica Ainscough

December 6, 2025 AT 03:58Brian Perry

December 6, 2025 AT 16:46Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 8, 2025 AT 11:31Paul Corcoran

December 8, 2025 AT 22:12Colin Mitchell

December 10, 2025 AT 09:36Stacy Natanielle

December 11, 2025 AT 13:13kelly mckeown

December 12, 2025 AT 16:39Tom Costello

December 13, 2025 AT 17:57Susan Haboustak

December 15, 2025 AT 11:18Siddharth Notani

December 16, 2025 AT 00:08Akash Sharma

December 16, 2025 AT 06:35Justin Hampton

December 16, 2025 AT 18:39