Medication Safety Reporting Disparity Calculator

Your Patient Profile

Reporting Disparity Analysis

Enter patient details to see their medication error reporting disparity

Medication errors don’t affect everyone the same way

Every year, millions of people around the world suffer harm from medications that should have kept them safe. But if you’re Black, Hispanic, elderly, non-English speaking, or low-income, your risk isn’t just higher-it’s systematically ignored. While hospitals track medication mistakes, the data hides a troubling truth: some patients are far less likely to have their errors reported, noticed, or fixed. This isn’t about bad luck. It’s about broken systems that fail the people who need safety the most.

Why some patients’ errors never get recorded

In a 2021 study across five NHS hospitals, researchers found that patients from white or Black ethnic backgrounds were far more likely to have medication incidents reported than those from other minority groups. That doesn’t mean those groups make fewer mistakes. It means their concerns vanish. A Spanish-speaking elder misreads their pill label. A Native American patient hesitates to question a doctor’s prescription because they’ve been dismissed before. A Vietnamese grandmother skips doses because she can’t afford them-and no one asks why.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re symptoms of deeper gaps: language barriers, cultural mistrust, and clinical bias. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open confirmed that clinicians often assume minority patients won’t understand complex instructions, so they simplify-or skip-critical safety steps. Others assume patients won’t speak up, so they don’t check for understanding. The result? Errors go unreported because the system doesn’t expect them to be raised in the first place.

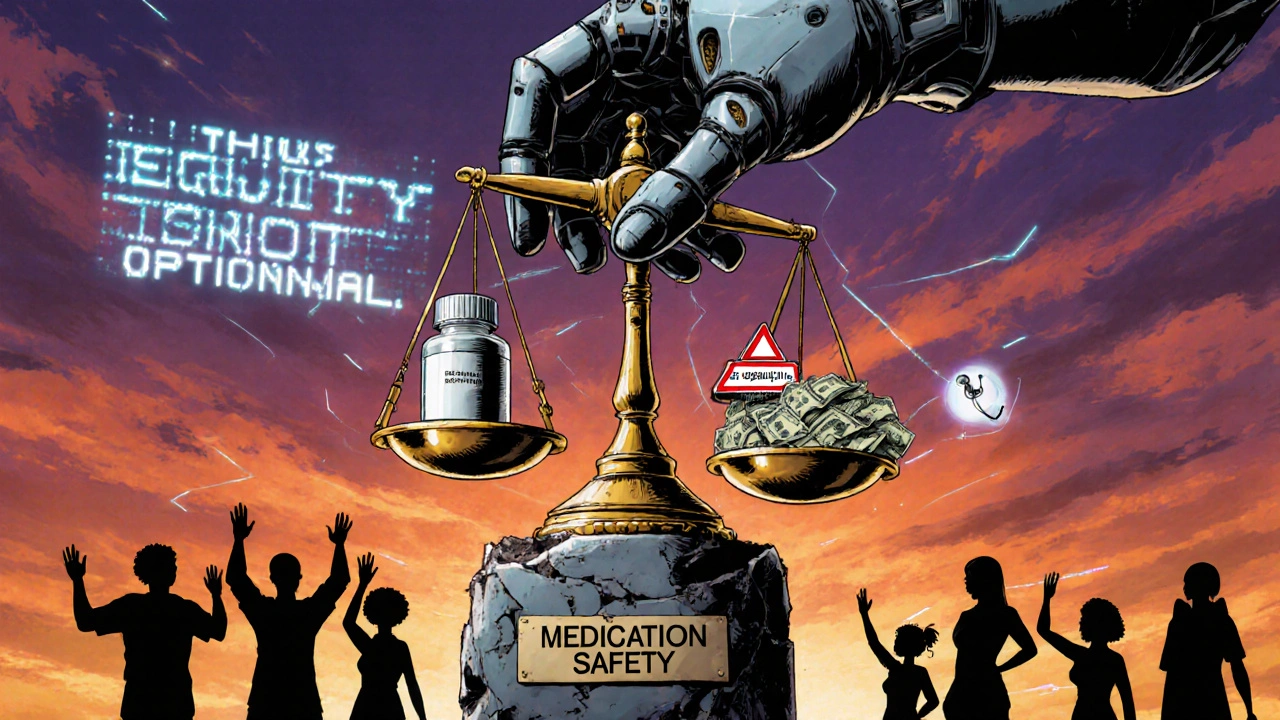

Who gets left out of clinical trials-and why it kills

New drugs are tested mostly on white, middle-class men. That’s not just unfair-it’s dangerous. Between 2014 and 2021, Black Americans made up just one-third of participants in clinical trials, despite having higher rates of the diseases those drugs were meant to treat. When a medication is only tested on one group, side effects in others go unnoticed. A blood thinner might cause dangerous bleeding in Hispanic patients. A diabetes drug might be less effective in Asian populations. But without diverse trials, we never know.

The consequences are deadly. In 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force couldn’t issue specific colorectal cancer screening guidelines for Black patients-even though they die from it at the highest rates-because there wasn’t enough data from Black participants in past studies. That’s not science. That’s negligence dressed up as caution.

Cost blocks safety, not just access

Even when a safer drug exists, it’s out of reach. In 2022, nearly 19% of Hispanic Americans and 11.5% of Black Americans had no health insurance. That’s compared to 7.4% of white Americans. When you’re choosing between rent and your insulin, you don’t ask your pharmacist about side effects-you just take what you can afford. Many turn to over-the-counter alternatives, herbal remedies, or skip doses entirely. These aren’t choices. They’re survival tactics. And they’re invisible to most medication safety systems.

High out-of-pocket costs don’t just limit access-they create silent errors. A patient takes half a pill because it’s all they can afford. A caregiver gives a child a sibling’s antibiotic because it’s cheaper than a doctor’s visit. These aren’t mistakes made by patients. They’re failures of a system that doesn’t design safety around real-life constraints.

Implicit bias isn’t a footnote-it’s the main cause

Doctors don’t wake up intending to harm Black or Indigenous patients. But unconscious bias shapes decisions every day. A 2024 study found that clinicians consistently underestimated pain in Black patients, leading to lower opioid prescriptions-even when medical records showed identical conditions. That same bias shows up in medication safety: a Black patient’s complaint about dizziness is dismissed as anxiety. A Hispanic patient’s confusion about dosage is labeled as noncompliance, not a language issue.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) calls this a patient safety crisis. And they’re right. Bias doesn’t just affect treatment-it affects reporting. When patients feel unheard, they stop speaking up. When staff assume they won’t understand, they stop explaining. The cycle tightens. And the harm grows.

What’s being done-and why it’s not enough

The World Health Organization launched ‘Medication Without Harm’ in 2017 to cut global medication errors by 50% by 2022. The goal was bold. The progress? Mixed. While 86 countries have pledged support, few have embedded equity into their plans. The Joint Commission added a new patient safety goal in 2024: improve equity. But only 32% of U.S. hospitals have formal programs to tackle medication safety disparities. The rest? They talk about it. They don’t fix it.

Some progress is happening. The U.S. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology launched a $15 million project in 2024 to build AI tools that detect disparities in electronic health records-like sudden drops in medication adherence among elderly patients in low-income zip codes. But AI can’t fix bias if it’s trained on biased data. If past records show Black patients rarely report side effects, the algorithm learns to ignore those signals. That’s not innovation. That’s automation of neglect.

Real solutions need real change

There are no magic bullets. But there are proven steps:

- Language services aren’t optional-they’re lifesaving. Hospitals that offer trained medical interpreters see 40% fewer medication errors among non-English speakers.

- Standardized reporting must include demographics-not just to track numbers, but to spot patterns. Is error reporting dropping in neighborhoods with high immigrant populations? That’s a red flag.

- Cultural competency training must go beyond checklists. It needs real stories, real feedback from patients, and accountability. No more ‘we did the training’ without measuring if it changed behavior.

- Community health workers must be part of the team. People trust neighbors more than strangers in white coats. When a trusted local helps a patient understand their meds, errors drop.

- Drug pricing must be part of safety policy. If a medication is too expensive for a patient to take, it’s not safe. Period.

Dr. Mary Dixon-Woods at the University of Cambridge says it best: healthcare systems must review their processes with an equity lens as a routine part of care. Not as a side project. Not as a PR move. As a core function.

The bottom line: Safety isn’t neutral

Medication safety isn’t about pills and prescriptions. It’s about power, trust, and who gets heard. If your safety depends on how you look, how much you earn, or what language you speak, then the system isn’t broken-it was designed this way. Fixing it means admitting that. It means funding interpreters, not just apps. It means including diverse patients in trials, not just checking a box. It means listening when a patient says, ‘I didn’t take it because I couldn’t afford it,’ and then changing the system so they never have to say it again.

The data is clear. The harm is real. And the solutions? They’re not expensive. They’re just hard. And that’s why so few try.

Why are medication errors under-reported in minority communities?

Medication errors are under-reported in minority communities due to language barriers, cultural mistrust of healthcare providers, fear of being dismissed, and lack of access to clear, culturally relevant information. Patients often don’t know how or when to report errors, or they’ve had past experiences where their concerns were ignored. Studies show that implicit bias among clinicians also leads to fewer follow-ups and less thorough safety checks for patients from marginalized groups.

How does lack of diversity in clinical trials affect medication safety?

When clinical trials don’t include enough people of color, elderly patients, or those with chronic conditions common in marginalized groups, the safety data is incomplete. Side effects, drug interactions, and effective dosages can vary by race, ethnicity, and biology. For example, a heart medication might cause dangerous reactions in Black patients that were never detected because they made up less than 10% of trial participants. This leads to unsafe prescriptions and preventable harm.

Can artificial intelligence help reduce medication safety disparities?

AI has potential-but only if it’s built with equity in mind. Algorithms trained on biased data can reinforce existing disparities. For example, if past records show low reporting from Latino patients, an AI might assume they don’t have issues, and flag fewer alerts. The U.S. government is funding projects to detect disparities in electronic health records, but success depends on using diverse, representative data and involving affected communities in design. Without that, AI becomes a tool for automation, not justice.

What role does cost play in medication safety?

Cost is a direct safety issue. When patients can’t afford their prescriptions, they skip doses, split pills, or use expired or borrowed medications. In 2022, nearly 19% of Hispanic Americans and 11.5% of Black Americans were uninsured, compared to 7.4% of white Americans. This leads to uncontrolled conditions, emergency visits, and dangerous drug interactions. Safety systems that ignore cost are ignoring reality. Affordable access isn’t a social issue-it’s a clinical necessity.

What can hospitals do right now to improve medication safety for all patients?

Hospitals can start by hiring trained medical interpreters, not just translation apps. They can require demographic data in all incident reports to spot patterns. They can train staff in cultural humility-not just awareness-and tie performance reviews to equity outcomes. They can partner with community health workers to bridge gaps. And they can stop treating medication safety as just a technical problem-it’s a human one. Real change starts when systems stop assuming patients are the problem, and start asking: what’s wrong with our system?

Hope NewYork

October 31, 2025 AT 21:44Bonnie Sanders Bartlett

November 1, 2025 AT 19:36Melissa Delong

November 3, 2025 AT 10:12Marshall Washick

November 5, 2025 AT 06:11Abha Nakra

November 6, 2025 AT 17:48Neal Burton

November 8, 2025 AT 14:03Tamara Kayali Browne

November 9, 2025 AT 14:03Nishigandha Kanurkar

November 10, 2025 AT 13:06Lori Johnson

November 11, 2025 AT 16:47Tatiana Mathis

November 13, 2025 AT 13:33Michelle Lyons

November 13, 2025 AT 19:30